A short introduction to personal names in the Scandinavian Iron Age

Names, qualities and characteristics

When we get to know someone, one of the first things we learn about them is usually their name. As an archaeologist, you can get very close to prehistoric people. You excavate the remains of a house, to which the door once opened and closed several times a day, letting people walk in and out and through the rooms. We hold in our hands their personal objects such as tools and ornaments that are worn from long continued use. We even deal with remains of past people themselves, getting insights into their strenghts, ailments, travels and deaths. But their names are mostly unknown to us, and so prehistory stays strangely anonymous in spite of the intimacy we can gain from material remains.

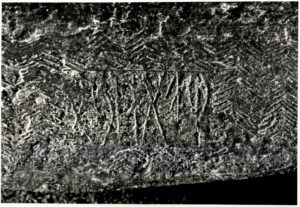

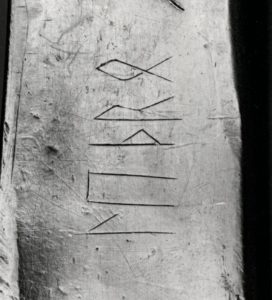

But names were important identity markers for past people as well as for us in the present. When runic writing first appears in Scandinavia in the Roman Iron Age, names and personal designations are the most prominent features of the often very short inscriptions. Before we even get rune stones, people started writing names on objects. In the beginning, these were mostly fibulae (clasps or brooches), weapons or other warriors’ equipment and tools. The names can be makers’ marks such as the inscription wagnijo found on three spearheads from bog deposits in Illerup and Vimose in Denmark. This name was stamped into the objects in the making and probably reflect a renowned and skilled weapon smith branding his products. Wagnijo is related to the modern Danish male name Vagn and has a root that is related to the word wagon, modern Scandinavian vogn/vagn, meaning something like ‘the one in motion’. As such, it resembles other names, such as harkilaz, derived from a word meaning ‘noise, uproar’, on a scabbard from Nydam bog. These names referring to abilities such as speed, strength, agility and noisiness reflect ideal qualities to warriors in the ways of Germanic tribal warfare. The designation wagnijo could however also refer to the weapon itself and its abilities. The inscription raunijaz, ‘tester’on the Øvre Stabu spearhead from a grave in Norway is interpreted as a name of the weapon. This poses us with one of the recurring problems when we get acquainted with the earliest known personal names. How do we know that they are indeed names?

Well, we often cannot be sure. It seems that words both from the general language and from poetic language fed into personal names. So, when we find an inscription like hagiradaz, on a wooden box from Garbølle, Zealand, we may se a name composed of two elements known from other personal names: adj. *hagi, ‘competent, skilled’ and a nomen agentis to Old Norse ráða, ‘give advice’. But there is also an adjective in Old Norse hagráðr, ‘good at giving advice’.

Some of these names give the impression that they were actually bynames or nicknames acquired during the life of an individual and thus maybe not given at birth(?) The person called lamo, ‘lame, the lame one’ who states that he/she cut the runes on the Skovgårde fibula could have had this disability from childhood. Another example, unwodz on the Gårdlösa fibula, meaning ‘the un-raging’ i.e. ‘the calm one’ could also be explained by this person being an unusually well behaved baby. Should we however think that leþro, ‘the leathery one’ who probably wrote his/her name on the Strårup neck ring got this characteristic quality later on? And what about swarta, ‘the black one’ on a shield handle from Illerup?

The above mentioned Lamo and Lethro are both names on objects that are traditionally connected with the female sphere, however they are part of a group of names ending in -o, representing linguistic forms that are very disputed as to whether they are local Proto-Scandinavian feminine names. They could also be masculine names, in this case maybe West Germanic or a relic of older forms. If they are female names, they could be the names belonging to the owners of the objects, however, Lisbeth Imer among others has made the case that they were actually inscriptions referring to the makers or the rune-writers.

In a recent article, Michael Schulte has discussed some of the character-describing names in relation to inscriptions with the word erilaz/irilaz. Schultes main message is that raskaz on the recently found Øverby/Rakkestad rune stone is probably a personal name or byname meaning ‘the quick/swift one’. This is in opposition to the newly published reading of the inscription that sees raskaz an adjective to the word irilaz meaning ‘clever, skilled’. I quite agree with Schulte here, especially in view of other quality-describing names or by-names. On the By-stone we find the runes hrōzaz ʻthe mobile, quick oneʼ in relation to irilaz.

Schulte importantly points out that these names that describe motion and swiftnes seem related to weapons and erilaz/irilaz-inscriptions. He also mentions wagigaz on the Rosseland stone and wagaz (dat. sg. wage) on the Opedal stone, both with a root related to the above mentioned wagnijo. On the Reistad stone there is a wakraz, from an adjective meaning ‘awake, quick, attentive’. To these we may add names that denote noisiness like the above mentioned harkilaz or another example rawsijo, ‘roaring, noisy, uneasy’ on a mount from Nydam. Apparently the ideal warrior was noisy and quick.

The meaning of the word erilaz is disputed, but it seems to have been some sort of military leader who also often had knowledge of runes. The erilaz-inscriptions are found on rune stones, gold bracteates and other objects such as weapons. Furthermore there seems to be a linguistic connection between erilaz and the word jarl, English earl, although this connection is not a straight forward development from erilaz to jarl. Together with Krister Vasshus from UiB, I am working on a small text about earls in Scandinavian place names, so stay tuned.

Further reading:

Article by Lisbeth Imer about maker’s marks on Roman objects and in runic inscriptions: https://www.academia.edu/1778049/Maturus_fecit_-_Unwod_made._Runic_Inscriptions_on_Fibulae_in_the_Late_Roman_Iron_Age

Article by Michael Schulte about names or by-names and erilaz-inscriptions: http://scandphil.spbu.ru/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Schulte-M.-Raskhet-i-de-eldre-runeinnskrifter.-En-runologisk-og-lingvistisk-kommentar-til-den-nyfunne-Rakkestadsteinen-fra-Øverby-i-Østfold-1.pdf