Iron Age naming behavior and warrior identity

Scandinavian Iron and Viking Age people had a strong fascination of the wolf and seem to great extend to have identified themselves with this animal. Wolf symbolism played a key part in the world perception.This can be concluded from both mythology, artwork and naming behavior, together stretching over a very long period. Already in the 3rd c. AD, we find a name, Widuhundaz on an elaborate silver brooch from Himlingøje, Zealand. This name is a compound of the words ‘wood/forest’ and ‘dog’ and are thought to refer to the wolf. The brooch was part of the funerary attire of a rich woman, but Widuhundaz is a male name, and this man was probably the maker or commissioner of the brooch.

From the 5th c. on, we begin to get a distinct form of visual expression in Scandinavia, called animal art. From early on, the wolf is a recurring motif, for example on the weaponry found in Nydam Bog in Denmark. Wolves continue to be prominent in iconography through both the Iron Age and the Viking Age. Read more about wolves in Iron Age iconography here.

Wolves in Old Norse mythology

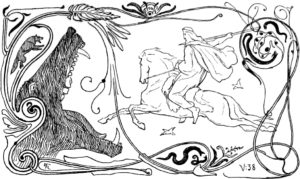

In Old Norse mythology, the wolf, as one of the scavengers that would raid a battlefield after the fighting, was seen as closely connected to the god Odin. Odin is flanked by the wolves Geri and Freki (both meaning ‘greedy’), along with two ravens, also battlefield scavengers. Wolves further functioned as embodiments of natural powers, chaotic and destructive forces and were associated with wilderness, forests and outlands as well as with giants. Central in the mythology was the enormous wolf Fenrir, a name meaning ‘swamp/marsh-dweller’. In an important mythical scene, Fenrir bites off the hand of the god Týr thereby challenging the world order. This scene seems to be depicted already in the 5th c. In the myths, this wolf is destined to kill Odin in the final battle, thereafter proceeding to swallow the sun.

While wolves represented strong cosmological powers in the myths, they could also be associated with the ideal identity of the warrior and with personal qualities and kinship. The social behavior of wolves, hunting in hierarchical packs probably served as a point of reference for the warrior bands of Iron Age Northern Europe – but this phenomenon is known from other cultures as well (such as Ancient Greece). Some scholars argue that these war bands may have had initiation rituals of young male warriors involving imitating or behaving as wolves. This is thought to be reflected in Vølsungesaga, where Sigmund and his son/nephew Sinfjøtle live for a period as outlaws and could shape-shift into wolves.

Animal identities and names

Animals in general played a key part in the Iron Age world perception, something recently taken up in an exhibition at Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo. Animal symbolism was a part of all forms of expression, poetry, metalwork, woodwork, textiles and garments and rituals. The fascination of and self-identification with animals also comes through in the use of words for animals in personal names. The animals most represented in visual artwork correspond closely to the ones that figure in naming. These can all be tied to war, battle and the ideals of warrior life and identity: birds of prey, horses, boars, wolves, bears and snakes. The words for animals are often combined with another word (often related to war and battle) into a compounded name. In pre-Viking Age runic inscriptions, the wolf is the animal that occurs most often in names. In Viking Age inscriptions, the element is also very common, used both as first and last elements and is attested as a simplex, Ulfʀ, no less than 89 times (some are believed to refer to the same person).

Wolf-man hybrids

Hybrids between humans and animals are a key trait of the Scandinavian pre-Christian belief system and this may have played a part in the use of animals in personal names. In the myths, both gods and even some people can change their hamr, their physical manifestation and appearance – as Sigmund and Sinfjøtle mentioned above. Dressing as animals can also have been used to create effects in both ritual situations and in battle. A few images from the Late Iron Age depict a warrior wearing a wolf costume, holding a lance and a sword.

These images have been connected with the later texts mentioning warriors clad in wolf-pelts called ulfheðnar, literally ‘wolf-skins’. These are sometimes seen as a wolf-variant of the berserker-warriors. There are of course many issues to be aware of when we try to connect Old Norse poetical or narrative sources that were written down in the Medieval Period with much earlier concepts and ritual practices. However, ideas about blending between species and/or the absorbing or embodiment of certain animal qualities were probably already in play in the Iron Age and may have been key motivations for using words for animals in personal names. An anonymous written source from the 5th or 6th century, the Opus imperfectum in Maetthaeum, criticises the naming customs of barbarians near the Danube, that are assumed to have been Germanic:

”they use to give names to their sons in accordance with the devastations of wild beasts and birds of prey, regarding it a source of pride to have such sons, fit for war and raving for blood” (translation from G. Green 1998).

In my research so far, I have identified two basic motivations for name choice in elite/warrior groups of this era: One is the fulfillment of the meaning of the name, where the semantic meaning was meant to assign qualities to the person as illustrated in the quote above. The other is to transfer qualities from or even revive (the power of) an ancestor. The last purpose was fulfilled through a tradition where a person was named using a name element from another family member, rather than a whole name. Certain name elements became inherent in some families, but were recombined in ever new compounds. This is called variation naming.

Wolf-clan families?

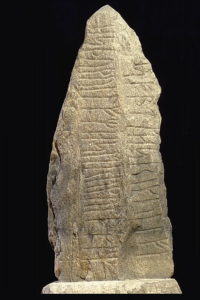

The best example of variation naming in a family is known from a group of rune stones from Blekinge, Sweden, from around the 7th century, the Istaby, Stentoften and Gummarp stones (DR 359, 357 and 358). They mention three related males Haþuwulfaz, Hariwulfaz and Heruwulfaz. This must have been a local ruling family or clan, and they marked their presence by erecting several monuments in the area. The names express their group identity through alliterations with h-sounds and through the repeated second element wulfaz, ‘wolf’. They are combinations of respectively battle+wolf, warrior/war host+wolf and sword+wolf. These names underscore how the Iron Age warrior ideal was closely connected with poetic ways of expression. Both Hariwulfaz and Heruwulfaz, ‘warrior/army-wolf’ and ‘sword-wolf’, have counterparts in the Old English poetic warrior designations, herewulf and heoruwulf.

The men on the Blekinge stones may even have belonged to a clan or tribe that associated themselves particularly with the wolf. Another stone, Sö 88 from Valby, Öja Socken in Södermanland from the 11th c. features one more family who favored wolf elements in their names: the stone has the text (extracted from the database Runor at Riksantikvarieämbetet Runor (raa.se):

Steinn, Fastulfr (and) Herjulfr raised this stone in memory of Gelfr, their father, and in memory of Ulfviðr, Gelfr’s brother. Holmlaug’s able sons made the monument.

Two of the sons, Fastulfr, (strong/steady+wolf) and Herjulf (warrior/war host+ wolf) have wolf-names, while the father and uncle also have variations of the same theme. Although less obvious, the name Gelfr is probably a contracted form of Gæiʀulfrʀ (spear+wolf) and the brother of the father has the name Ulfviðr (wolf + wood/forest).

Although the wolf was commonly used as a name element, especially in Viking Age inscriptions, these two families who used multiple wolf names show us that sometimes, the wolf association may have been part of the collective definition of group identity, defining kinship or clan membership and reaching beyond individual personal qualities.

Pingback: Hariwulfaz/ Hariulf/Hærulf – a trendy name in the 5th-11th centuries – ArcNames